Stephanie Hunt |

Stephanie Hunt |  Sun, June 3, 2012 at 13:05 |

Sun, June 3, 2012 at 13:05 | Willis tells me that the most interesting person he knows is Charlie Saunders, one of his former students at the TAFE. Willis assures me that Charlie has more stories than the Times and boy is he right. Having regaled me with his tales, Charlie then nominates his brother Don Saunders as the most interesting person he knows. I head out to Bonville to talk to Don and quickly realise that the brother’s stories are wonderfully entwined. These stories need to be told together.

******************************************************************

From the moment Don and Charlie Saunders begin to tell their tales it is apparent that these stories must be told in their own words. A big city Sheila like me just couldn’t translate. Listen to their voices and feel yourself transported to another place and time.

We start with growing up in Warren, a small agricultural town west of Dubbo. Much of this world is long ago lost. Don and Charlie’s tales of adventure, rivers and hard times are reminiscent of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn...different river, different accents, same narrative of boyhood exploits and discovery.

So sit back and enjoy the adventures. If any of you fellow city slickers, Gen Ys or new migrants get confused by the language, check out the “Learn to Speak Like an Outback Aussie” glossary at the bottom. And if the odd bit of bad language bothers you, please don’t read any further.

Growing Up in the Wild West

Growing Up in the Wild West

DON

I’m ‘42 drop*, Charlie’s ‘48. So I’m six years older.

I remember my Granddad; he died when I was about 10. He had built a power station in Warren back in the late 20s. We were only the second country town onto commercial power thanks to Granddad. I remember the old steam engine at the power station. They replaced it with a diesel engine sometime after the War. Huge, big, green, noisy thing … frightened the crap out of me. Granddad also sank a bore to 1800 feet. It flowed 500,000 gallons a day and was reticulated right round the town.

We weren’t a wealthy family at all. We struggled half the time. Dad used to sink the bores after he and Granddad sold the power station. If it rained and the wool price was good they had plenty of work, but during droughts the farmers had no money for bores. It was an up and down sort of a life. But Dad would just borrow a bit more from the bank. Somehow there was always plenty of tucker*and enough money left to educate the four billylids*.

We used to go rabbiting* when I was a kid. The rabbits would dig burrows in the sandy loam. But when the rabbits are really thick there’s not enough feed on the sandy country so they move out onto the black soil. They hide in roly polies* and hollow logs and you just bundy* em. They were everywhere, thousands of them. They’d have a 400 yard wide line of us kids with tins and a stick walking along rattling the tins and hunting the rabbit into a yard. We'd ring their necks and then gut and pair* them ready for the chiller.

When it rained my Dad and few other families would go out in the Ute picking mushrooms. On one mushrooming day, my sister and a mate and I went rabbiting away from the mushroom mob. I was 5 at the time. My sister panicked a bit and went back to where the others were. And when it got dusk me mate and I decided to go back too but we went the wrong way. We walked and we walked and we walked through the night. We walked along the top a fence that crossed a creek, got to the other side and walked some more. We came to this house, way to buggery* out of town, and the dogs started and we got frightened. We camped under a tree and the next day a guy on a horse found us. They had seen our tracks where we walked onto this fence to get across the creek and thought we might be in the creek. The search parties lit fires and had a small plane in the air the next morning, but hadn't seen any of that.

I went to school at Warren as Charlie did. I actually got the dux in third year. It’s still on the board out there somebody told me. They sent me away to boarding school for fifth year. I struggled academically when it got to a bigger school. But I loved it because of the sport.

I was 15 when the All Blacks came to Warren in 1957 and I played in the curtain raiser that day. Played rugby union from then on. When I was 16 I played first grade. I was tiny and they were big bloody* bastards. After boarding school, when I was 19, I went on a country zone rugby tour to NZ. I had a mentor that really wanted me to go to Sydney and play grade Union. But I had a job arranged in Warren and I didn’t have much money. To go to Sydney seemed a traumatic thought.

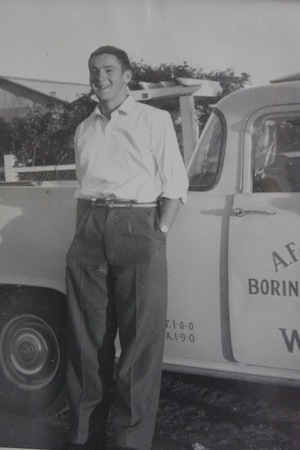

So I started working in the bush at Warren, living at home and learning to do bloody civil engineering by correspondence. Roads and bridges and water and sewage stuff… the town engineer.

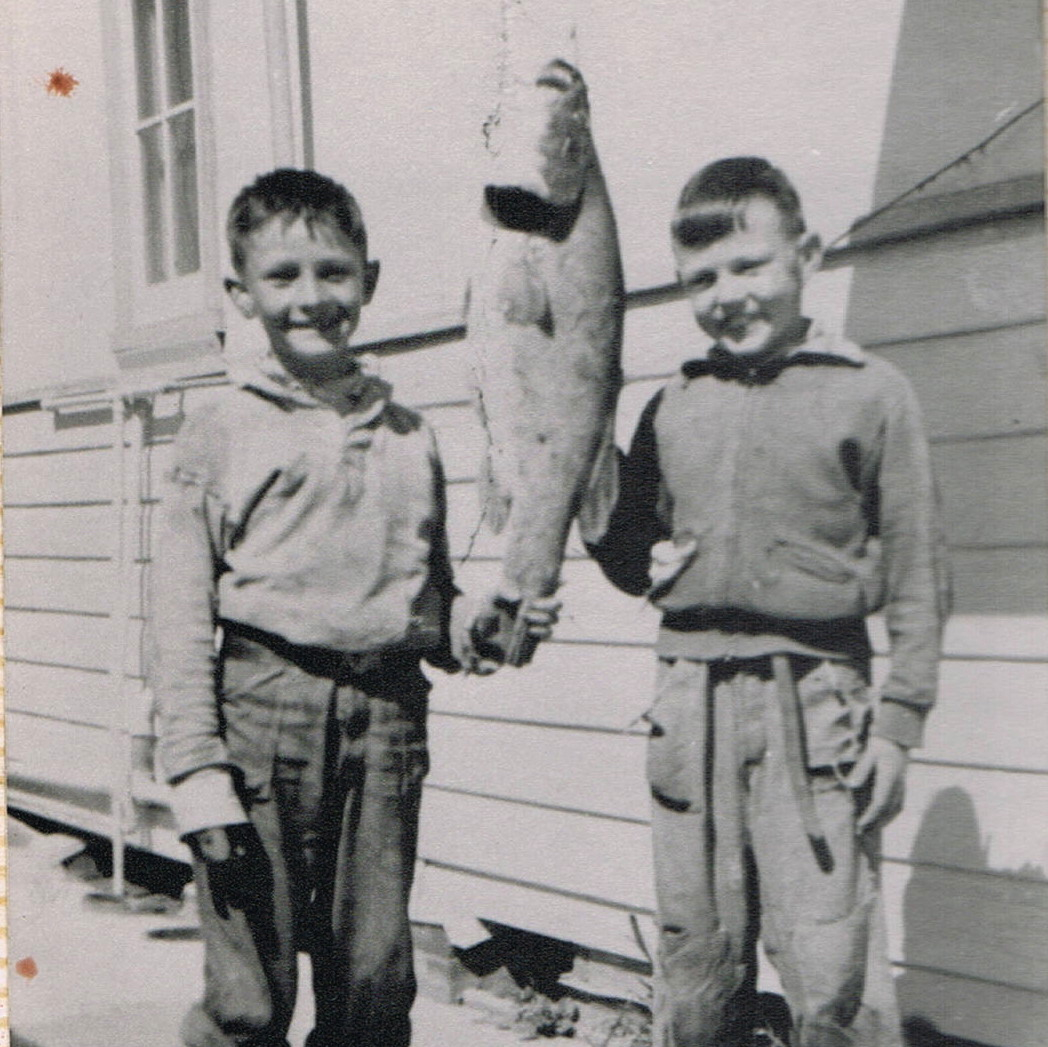

Charlie (right) with his cousin.CHARLIE

Charlie (right) with his cousin.CHARLIE

I was born in Warren, north-west of Dubbo in 1948. The population at that time was approximately 1200.

The Macquarie River runs through Warren. I used to fish on the riverbank with a cousin because his house was on the river. We loved pinching eggs from the hen houses and cooking them on the riverbank. Fishing was a major part of my life. I just loved fishing. I loved the outdoors.

When we were about 8 or 10 our parents would take us up the river and drop us off with a piece of tarp to make our tent. We would set our fishing lines for the night cook a feed while our parents had a drink. Then they would go back into town. They’d come back the next morning and we’d have all the fish ready for them, still alive and kicking. We would tether up the fish by their nose and throw them back in the water.

I remember one time when I was still very young and the river was running a banker, which means it was full but it hadn’t broken the banks. Me and some mates were standing there watching the water rush by and this big tree came floating down the river. So we stripped our gear off and swum out and jumped on the tree. By the time we realised, “Hello, what’s happening here?” we thought, “Doesn’t matter we’ll keep going.” One of the kids lived further down the river so when we got to his house we all jumped off and swam to the bank. By that time it was starting to get dark and all of Warren was out searching for us. All they’d found of us was our school bags and all our bloody clothes and they had no idea. I’ll tell you I was pretty worn out by the flogging I got that night.

I was one of the first to go through the Windham scheme. Prior to me going through high school was 5 years. Then when I went into first year they changed to the Windham scheme so my high school went to 6th year like it is now.

I went away to All Saints College in Bathurst - was school captain there for two years in a row (which is not common). I used to go to school on the steam train. The train used to go from Warren to Nevertire, which was 13 miles and then you’d change there and go to Bathurst.

I was a good sportsman. You name it, I did it. I excelled in running and I think I still have the record there. I ran in the imperial system and the metric system, so I think I still hold the record for the 100 yards: 10.1 seconds.

When school finished I just came home and I was going to work for Dad, I’d worked for him in the holidays anyway. It lasted one week and he sacked me because I knew more about his job than him. And that’s when I got into cotton.

A Young Don as Civil Engineer

A Young Don as Civil Engineer

Cotton Luck

DON

I went broke twice in two years.

I got the top engineering job for Warren Shire when I was 27, too young because I didn’t understand the politics. They put pressure on me and I walked out in ’72. By this time I was married to Trish and had one on the ground and one in the oven*. The super money ran out pretty quick. We had a tiny block of irrigation land on the outskirts of Warren, so I worked that and Dad lent me his ute* and I tried to do some irrigation surveying.

I started to make a few bob* and then I bought some cattle. Made a bob or two on them and the next year I bought lots and went broke again. Worst cattle sale in Australia’s history I reckon. Now I had two kids and I’d borrowed $18,000 off my Mum and $26,000 off the agent. In those days that was a lot of money.

I worked like buggery,*double cropped my irrigation land and Trish went back to teaching. We paid the money back. I started travelling to different towns for work, and that’s when I got going as an irrigation surveyor.

It’s not blowing my trumpet, but I surveyed most of the major projects in cotton throughout NSW and southern Queensland. We moved to Moree in 1980, built a new home and then I was really busy. I had 3 or 4 survey crews and it was just work, work, day, night, 7 days a week. We generated a lot of income and we were focussed on working, not on tax, so we paid a lot to the government.

So next door to me was an accountant called Mick Boyce, young fella into rural accounting. I had a beer with him and he said, “I’ve got this mate who lives in Mungindi on the Queensland border. He’s got a lot of land and water licenses but he’s not got a lot of cash.” Mick suggested that we form a farm partnership. I could put in the expertise and the money and his mate could put in the land and the water rights. The long and the short of it is we did that, while I was still working the survey and design practice.

Don at MungindiOver the years we built that farm up. I think we had 12000 acres of land and 5500 acres were irrigated. We weren’t really cashed up to cop a hit. Four thousand acres of cotton costs $4million to produce. If we had a failure through flood, drought, storm or pest we wouldn’t have survived. But we did it. My brother Charlie came out for 3 months and ended up staying for 6 or 7 years, which was handy for me ‘cause he could keep an eye on things while I kept the survey practice going full pace.

Don at MungindiOver the years we built that farm up. I think we had 12000 acres of land and 5500 acres were irrigated. We weren’t really cashed up to cop a hit. Four thousand acres of cotton costs $4million to produce. If we had a failure through flood, drought, storm or pest we wouldn’t have survived. But we did it. My brother Charlie came out for 3 months and ended up staying for 6 or 7 years, which was handy for me ‘cause he could keep an eye on things while I kept the survey practice going full pace.

After Charlie left we leased the farm for seven years to a big company. We didn’t have to do anything, just collect. And it was a very good collect. While it was leased we put some of that lease money back in and developed more land. Then when the lease ran out we sold it. The partnership needed to be broken up before one of us carked* it. The very next year the drought started. It went on and on and on and of course we would not have been able to handle that. Lucky.

I was living in Moree all this time, never moved to Mungindi. And I kept surveying, mainly in cotton. I was away a lot. I did that job at Lake Tandou at Menindee, 40 thousand acre lakebed. Cubbie Station out in Queensland: that was one of my early jobs. The government took me over to Thailand in ’77 to aid the rice farmers. I had a brief in Qatar to make them self sufficient in dairy products by irrigating the desert. I took on a large project in Argentina and travelled there 12 times in 3 years. Big jobs and they were all fighting for me.

Our house was just turmoil. The kitchen table would be full of maps. I’d have some client there with his offsider, and another client would arrive so I’d run into the garage, take the car out and set up the ping-pong table with another lot of maps. Occasionally we’d have to be in the lounge room and the dining room as well. Trish would have to get the kids fed and out of the way. It wasn’t funny. But it was exciting.

And I was lucky. But I think the harder I worked the luckier I got. I was lucky to find Trish. Lucky because I sold before the drought. Lucky with family. You need a bit of luck.

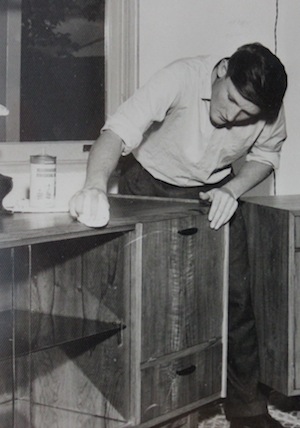

Charlie shows an early love of wood workCHARLIE

Charlie shows an early love of wood workCHARLIE

People tell me that I must have been born lucky. I walked into the pub one time and a bloke says, “Geez, you’re lucky.” And I said, “Why don’t you try working real hard to get a few quid. That’s what I did.” When I worked on the cotton we’d work seven days a week and if it didn’t rain you’d work every day for 3 months.

I went to work for Auscott in ‘68, a big American firm still going today. When I started I was a tractor driver, a crane driver and I worked in the workshop.

My brother had a property near Warren and I got involved in a partnership with him and a three other guys. We used to farm on the weekend and we’d work during the week. Then we got a bit big so I left Auscott in ‘75 and went to manage the property. By this time I had a wife and three kids.

But I loved fishing. So in 1980 I moved to Coffs Harbour to become a professional fisherman. My wife came over for a little while and then went straight back and that was the end of that. Then I met Margaret.

I couldn’t really make a go of the fishing. My brother Don and a partner had a farm in Mungindi. The property was really wet and they asked if I’d drive a grader for 10 days to help drain the water. So I loaded up the ute.

Tundunna Farm was a big sheep and wheat property, but about 5000 acres was going to be a cotton farm. I stayed on after the floods and took over managing the farm. That was ’84 and by 1990 when I left we had 4000 acres under irrigation.

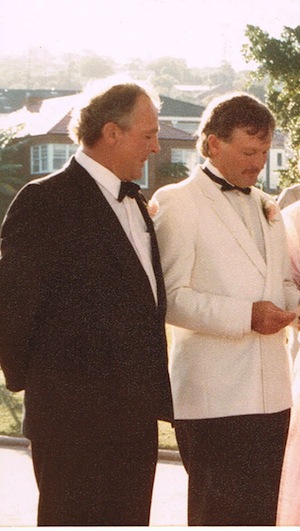

Don (left) and Charlie at Charlie's weddingMargaret had moved back to Sydney but she’d come up to visit. I could always tell when she was coming. Her headlights would be pointing to the sky because the boot of her car was full of cheap beer and alcohol for me. Then in ‘86 we got married and she came to Mungindi to live. City girl: never lived in the bush.

Don (left) and Charlie at Charlie's weddingMargaret had moved back to Sydney but she’d come up to visit. I could always tell when she was coming. Her headlights would be pointing to the sky because the boot of her car was full of cheap beer and alcohol for me. Then in ‘86 we got married and she came to Mungindi to live. City girl: never lived in the bush.

I’d built dams on the farm. The biggest one covered 300 acres and we used to go water-skiing and sailing. And Marg hated the mud with a passion. So she’d get her surfboards and line them up, then she’d wash her feet and try to walk back on the surfboards. We’d be pissing ourselves laughing.

Initially we had two share farmers. I’d get the fields ready for planting and the share farmers would come in and grow it. After about two years of that, we formed a partnership, my brother, his partner, myself and another good mate of theirs, so we could farm it ourselves. Then it became a very big job. I was building and developing the farm and growing the crop as well.

We had 3 major floods while I was there. Huge floods. You can’t go anywhere when it floods. You can only stay within the levy bank. There’s a very long water causeway that the floodwater goes over. There’s a pub that’s about two miles out of town and I thought we’d go have a meal. I got the vehicle fired up, put a wool pack around the front and lined her up. I was sober, well pretty sober. The water was lapping the top of the bonnet and we went off the road a bit. You could feel when it would drop off the bitumen. But we got there and we had a wow of a time; God we had a good time. Coming home very full, I lined her up and I never ran off the bitumen once.

They used to call me airplane farmer. I used to do a lot of trials using airplanes with fertilizers and chemicals and stuff. I remember one time I had lawn flees at the house. So I went to the chemical place and I rang the plane and said, “I’m coming out. We’re going to bomb the house to kill all these lawn fleas.” So we bomb, bomb, bombed this bloody house. There’s a really old wind generator out the front of the house and a dam out the back with big gum trees around it and the pilot’s flying in and around these. I was crook. I got home and all the chooks and the pigs weren’t feeling too good. Two days later the fleas were just as thick as they were before.

It was a big operation. I used to run 100 cotton chippers at picking time.

I could pump 5.5 million litres an hour out of the river. People perceive cotton to be one of the most high water use crops in forever but there’s lots of crops that use a lot more water that are grown in Australia. And the CSIRO and others have developed varieties of cotton that use less water & chemicals.

Then it became a chemical problem. The town’s people would complain and say, “Oh we can smell the chemicals.” The windsock would show the wind was blowing away from the town and still they’d complain. It got frustrating.

I left Mungindi in ’91. I was 43 and I basically retired. Came to Coffs Harbour, did some fishing. The timing was good because the greenies were going crook. In the end I just wanted to get out of there. But I had loved the cotton: doing 12, 13, 14 hours a day, having a drink and waking up going, “Geez, I’ve gotta do all that again.” That’s how I got lucky.

There are so many more stories of Don and Charlie that someone needs to write a book (seriously). Both men are now retired in the Coffs area, although retired is probably not the right word since Charlie is busy carving beautiful furniture and Don remains invested in a large abattoir in Cooma.

Learn to Speak Like an Outback Aussie

TRANSLATIONS AND CLARIFICATIONS

Billylids: Rhyming slang for kids, children

Bloody: Used to indicate that you dislike or disapprove of something very much as in “It’s bloody raining”, also used to mean very, as in “this is bloody good”.

Bob: Money, to “have a few bob” is to have some money

Bundy: A small stick. Also used as a verb – “to bundy” is to hit with a stick.

Cark: To die (interestingly this is possibly a shortening of carcass)

Drop: To give birth, as in “the cow dropped her calf”

Dux: Top of the class

Gut & Pair: Preparation for rabbits, includes removing the intestines (except the kidneys) then joining the two rabbits together by the hind legs

One in the Oven: Pregnant, expecting a child.

Rabbiting: Hunting rabbits

Roly Poly: Tumbleweed

Sink a bore: To drill into an aquifer to allow water to rise to the surface

Tucker: Food.

Ute: A coupe utility vehicle, a two-door coupe with a cargo be behind the cabin

Way to buggery: A long way away

Work like Buggery: To work hard

************************************************************

Don tells me that the most interesting chap he knows is a fellow named Ian Furze. “He’s an ex-bank-manager. He’s ex a lot of things.” I am sad to leave the stories of Don and Charlie behind, but looking forward to finding out about all the tales of Ian Furze.

Stephanie Hunt |

Stephanie Hunt |  Sun, June 3, 2012 at 13:05 |

Sun, June 3, 2012 at 13:05 |

Reader Comments (4)

Charlie and Don you have not changed proud to know you

there is no dought about it you 2 blokes are TWO Pea's in a pod. Chief dont forget in the next episode to include your Japanese mate who we run into at the sydney wentworth hotel remember he worked for YAMAHA. You were saying to him !!!! Vroom,vroom, and he said!!!!!!

No Yamaha piano's, LOL

You are both good blokes but wont share your winners with ole Bomber.

Cheers

Good grief Bomber. I missed out on the story about the Japanese mate entirely! Too many stories......